The week of March 9th was a slow chipping away at all that structured my life as an MFA student. Classes moved online, my thesis review and exhibition became a question mark, and grads were ordered to leave their studios. It felt like my cohort community was evaporating without warning or ceremony; I felt heartbroken and entirely disoriented. COVID-19 had only recently touched down in the U.S., and the reality of its danger hadn’t yet sunk in—nor had the reality of a global economic crisis.

Two experiences that week stand out from the haze. On Thursday, I visited an older artist’s home studio. I saw her magnificent, abstract drawings and paintings spanning decades and two coasts, as well as the precious works she’d collected over the years from friends. Secondly, on Friday, one of my professors was making harmonograph drawings in the school lobby with any one who chanced to pass by and show interest. I stopped to make one and was quickly lifted by the perfection of the machine, the beauty of the drawings, and the persistence of my mentor’s rational mind amidst the insanity of the moment. In both cases, I felt healed by a generosity coiled like a spring within thoughtful, beautiful art.

I’ve always been skeptical of how useful we artists really are to society. I think a good deal about whether art should serve as a call to action in troubled times, and if rather than being “moving,” art should move its viewers to act. But my experiences the week of March 9th gave me new perspective.

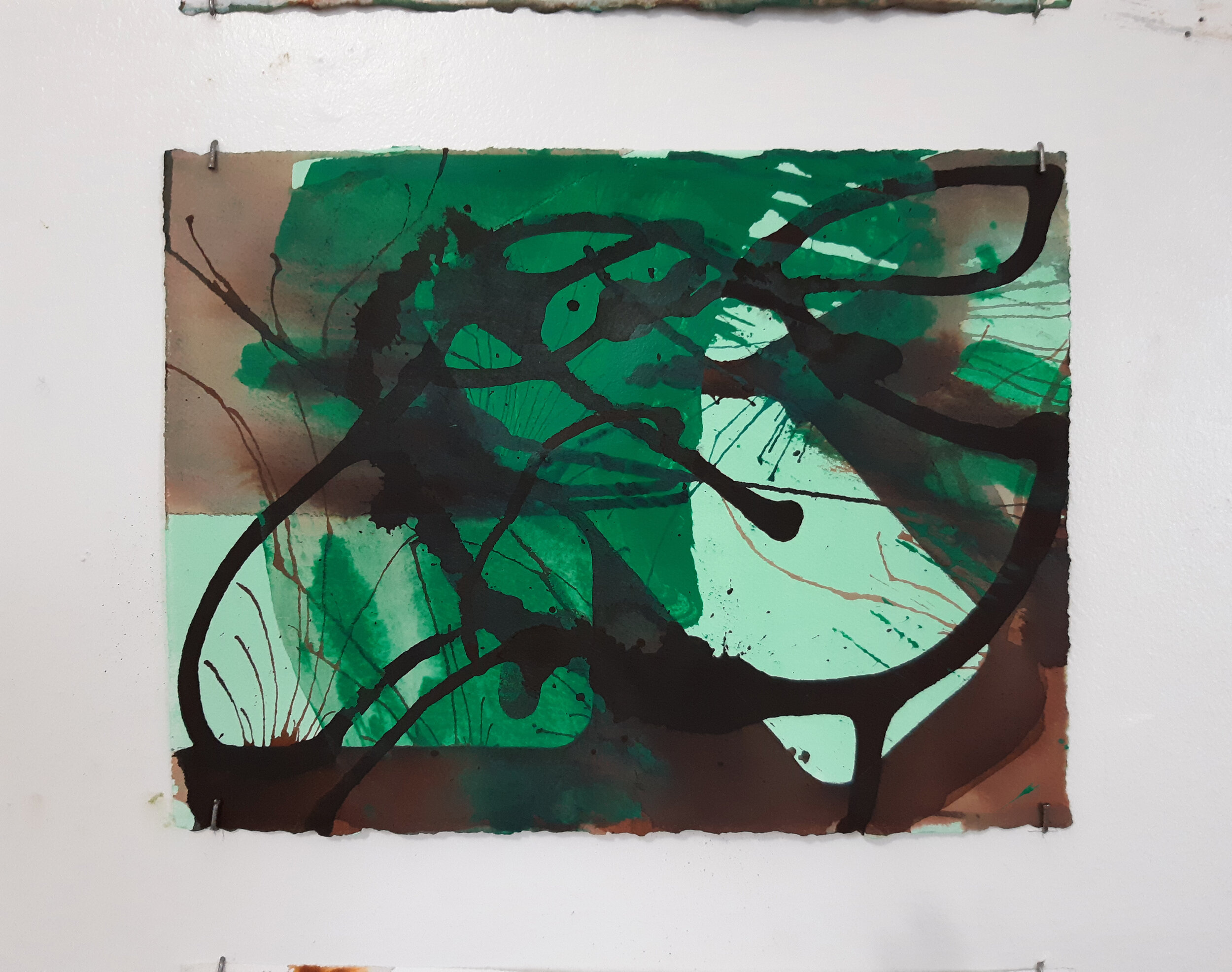

Since March 17th, I’ve spent a good portion of each day working on abstract drawings in a cleared-out corner of the house. It’s important to acknowledge my privilege, here. No one in my family is sick, I have a stable home and a nourishing partnership with my husband, and we have a little bit of savings. Not all artists have the capacity to make work right now, and I count myself blessed. The drawings make use of random, leftover materials that I distractedly grabbed from my studio before the school locked its doors, or that I happened to have lying around the house. This includes a few colors of ink and dye, some green latex house paint, and a bit of half-dried orange acrylic. Fortuitously, I had a stack of 9” x 12” watercolor paper in the house, leftover from a workshop that I taught this fall with poor attendance. These are parameters born of necessity, stores are closed and money is tight. But it feels poignant to work with materials that I don’t have control over, to figure out how to make use of what’s at hand (as artists have done for centuries). In 2016, at the Architectural Association School of Architecture in London, Brian Eno gave a lecture where he talked about art as a way for people to rehearse the critical life skill of negotiating between control and surrender, or going with the flow. I think that’s right. Drawing through the pandemic creates space for me to process what’s happening, while it exercises the mental faculties that we all need to face this moment—to be nimble, to control what we can and accept what we cannot.